Rebooting the immune system: Blood stem cells in multiple sclerosis therapy

As part of an international clinical trial, researchers at the Sheffield Teaching Hospital recently reported interesting developments in multiple sclerosis therapy. Using the patients’ own blood stem cells, the scientists were able to reboot their immune system, therefore preventing autoreactive immune cells from further attacks on their fragile nervous system.

How often do you think of the vast electricity grid spanning the whole country and right into your living room where it allows you to switch on the lights with just a tiny flick of your finger? Maybe not so often – until the next power cut leaves you in the dark.

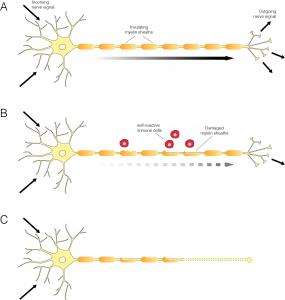

A similar system of ‘wires’, our nerve cells, allows us to tackle countless tasks every day. Whatever movement we make, there are electrical signals sent from our brain down the spine to the limbs. Those signals travel along long extensions of the nerve cells, so called axons. Exactly like an electrical wire, those axons need to be insulated to transmit their signals as fast and reliably as possible. In our body, the insulation is made of a fatty substance called myelin. These myelin sheets wrap themselves around axons like a blanket. But if they get damaged or lost, the nerve signals can’t be transported properly anymore – a little power cut inside the body occurs.

For a person affected by multiple sclerosis (MS), those black outs can turn every movement into a challenge. In their bodies, the myelin sheets get damaged by their own immune system. Their immune cells cannot distinguish between friend or foe anymore. And instead of fighting off harmful germs, they attack the body’s own myelin sheets, leading to recurring inflammations in the brain and spinal chord. Just like an inflamed scratch on our skin, the inflammation of the nerve tissue leaves scars – hence the name, multiple sclerosis or ‘many scars’. In the end, axons miss their myelin blanket, nerve signals get leaky and can’t be transported properly anymore.

For a person affected by multiple sclerosis (MS), those black outs can turn every movement into a challenge. In their bodies, the myelin sheets get damaged by their own immune system. Their immune cells cannot distinguish between friend or foe anymore. And instead of fighting off harmful germs, they attack the body’s own myelin sheets, leading to recurring inflammations in the brain and spinal chord. Just like an inflamed scratch on our skin, the inflammation of the nerve tissue leaves scars – hence the name, multiple sclerosis or ‘many scars’. In the end, axons miss their myelin blanket, nerve signals get leaky and can’t be transported properly anymore.

Currently there are 700,000 patients with MS in Europe most of them diagnosed in their 20s to 40s. It remains unclear what causes the disease: Scientists believe it is a mix of genetic and environmental factors, but how these factors contribute to MS is yet unknown.

Most patients only see a doctor after they discover first symptoms. At this point, the inflammation in the brain or spinal chord is already extensive and therefore makes it hard for doctors to establish how it was triggered in the first place.

There are different types of MS: the relapsing remitting (RR) type, where patients experience attacks of severe symptoms interleaved with periods of remission, and primary progressive MS, where people progress from one attack to the next with their symptoms getting progressively worse. Despite available treatment options, most RR MS patients will develop a secondary progressive form of the disease after many years.

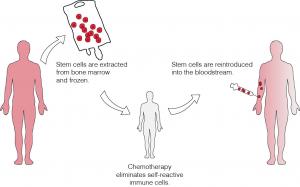

Now researchers at the Sheffield Teaching Hospital have reported interesting results for MS therapy. With a treatment conventionally used for cancer patients, they were able to reboot the patients’ immune system to a point in time before it turned against their own bodies. This autologous haematopoietic stem cell therapy (AHSCT) might even stop MS in its tracks. The therapy relies on the ability of blood stem cells (or haematopoietic stem cells, HSCs to build all the cells of the immune system. ‘Autologous’ stands for ‘related to self’ and means that the patient’s own blood stem cells are used. In AHSCT, very intensive chemotherapy first deletes the person's immune system. This chemotherapy is mixed with growth hormones, which coax the blood stem cells out of the bone marrow and into the bloodstream. Once enough of them are floating freely in the blood, the HSCs can be collected and stored in super cold conditions at around -200˚C to keep them fresh until the patients’ immune system is completely wiped out. Only then are the blood stem cells transferred back into the patient to build the new immune system from scratch.

Now researchers at the Sheffield Teaching Hospital have reported interesting results for MS therapy. With a treatment conventionally used for cancer patients, they were able to reboot the patients’ immune system to a point in time before it turned against their own bodies. This autologous haematopoietic stem cell therapy (AHSCT) might even stop MS in its tracks. The therapy relies on the ability of blood stem cells (or haematopoietic stem cells, HSCs to build all the cells of the immune system. ‘Autologous’ stands for ‘related to self’ and means that the patient’s own blood stem cells are used. In AHSCT, very intensive chemotherapy first deletes the person's immune system. This chemotherapy is mixed with growth hormones, which coax the blood stem cells out of the bone marrow and into the bloodstream. Once enough of them are floating freely in the blood, the HSCs can be collected and stored in super cold conditions at around -200˚C to keep them fresh until the patients’ immune system is completely wiped out. Only then are the blood stem cells transferred back into the patient to build the new immune system from scratch.

Although MS can be halted and some disabilities reverted by this treatment, there are limits due to the damage already done. The scars or lesions already left by the disease are not reversed, as there are no neural stem cells involved to build new nerve cells or myelin sheets. However, people with MS treated in the clinical trial reported that they were symptom-free and some had recovered their ability to walk or use their hands again. The long term effects of the treatment are still not clear, though.

So why do the new immune cells not attack again? Scientists still struggle to find a definite answer. Some studies even showed that the autoreactive immune cells are still present. But interestingly not all of the aggressive cells seem to recover: A small subset of killer cells, which could open the gates to the brain for other aggressive autoimmune cells, is much lower after AHSCT.

Although AHSCT was only successful for the relapsing remitting type of MS, it shows that MS treatment has come a long way. It was only 20 years ago, that the first drugs directly targeting the overactive immune system of MS patients and not only the symptoms entered the market. AHSCT has been explored as a treatment for MS since the 1990s in smaller scale studies. The Phase III study now underway in Sheffield and other collaborating centres around the world is a joint effort to systematically treat a larger group of different people with MS. The study will collect data until the end of 2017 and follow their disease progression for another five years. Although it is still not possible to cure the disease, the recent clinical trial for AHTSC could potentially establish a mainstream treatment once the long-term effects of the therapy are clear. And even more: understanding the basic principles of the therapy might help deepen knowledge of MS as a disease in the future.

Further information

- Further information about the clinical trial for AHSCT in MS at the Sheffield Teaching Hospital

- MS International Federation - http://www.msif.org

- Multiple Sclerosis Society - https://www.mssociety.org.uk

- Multiple Sclerosis Trust - https://www.mstrust.org.uk

- Links to articles cited (subscription may be required): Darlington, P. J. et al. Diminished Th17 (not Th1) responses underlie multiple sclerosis disease abrogation after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Neurol. 73, 341–354 (2013).

This is a guest post by:

Updated by: Sabine Gogolok

Last updated: