Interview with Henrik Semb: the pancreas, beta cells and diabetes

Professor Henrik Semb is the director of the Danish stem cell center. His research group focuses on how organs are formed and cells acquire their fates in vivo. In particular, they are interested in how processes such as cell shape changes, movement and polarity, not only affect 3D architecture of the developing organ but also what type of cells are made. In vivo findings from their lab have given insight into coaxing human pluripotent stem cells into functional insulin-producing beta cells as a source for therapy in type 1 diabetes.

Where did you start your research career and what journey have you taken?

It’s definitely not a straight line. I initially started studying medicine; I carried out my preclinical studies in Umeå, Sweden. But I found myself bored because nothing was really in depth; it was just constant studying for exams. It was here I thought of doing a PhD but I had never planned to be a researcher; I always wanted to be a physician.

"The intense, dynamic and sharing atmosphere with scientists from all over the world was very important to me; without it I cannot thrive as a scientist."

My PhD was on the regulation of lipoprotein lipase, which breaks down a type of fat, called triglycerides, in blood. Following my PhD I got really interested in cell biology and molecular biology. So I did a post-doc in UCSF, San Francisco with the aim of studying how molecules move through the cell via membrane-enclosed vesicles (membrane trafficking). My plan at that time was to complete my post-doc and then maybe go back into medicine; I didn’t really know what to do. But looking back, that was the best time in my career; it was the early nineties when Harold Varmus and Mike Bishop got the Nobel Prize, the working environment was amazing. For me, it was a shock to work somewhere with so many famous researchers, always open to a discussion. The intense, dynamic and sharing atmosphere with scientists from all over the world was very important to me; without it I cannot thrive as a scientist.

My research quickly moved from membrane trafficking to developmental biology using pancreas development as a model for how organs are formed. Initially, the focus on the pancreas had nothing to do with my interest in diabetes. I simply became fascinated by how organs formed. The availability of a technology that allowed us to turn specific genes on and off in different cell types, allowed us to ask specific questions about how tissues are formed in vivo. Doug Hanahan taught me how to carry out pronuclear injections. Learning this technology turned out to be useful for pursuing my growing interest in developmental biology upon my return to Umeå to start up my own lab.

When did you get interested in diabetes?

Initially I found it very difficult, especially starting up in a very competitive field. I struggled for a while in Umeå and found it hard to get grants and further positions. So I decided to move to another developmental biology environment at Gothenburg University. Here my expertise was considered valuable, things changed completely and my projects started to work much better; things were looking up. My original interest in medicine re-surfaced through a commitment to use our knowledge of how insulin-producing beta cells are born during embryo development to generate mature beta cells from pluripotent stem cells, such as human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). The long-term perspective was to use these cells in future cell-replacement therapy in type 1 diabetes. This was the first time I applied developmental biology to something clinically relevant and that’s how I got involved in the translational aspects of research.

Read more in our factsheet

Diabetes: how could stem cells help?

At this point I had two lines of research, firstly basic developmental biology to study how organs form, and secondly how to change hESC into beta cells as a source of transplantable cells to treat type 1 diabetes. The main changes since then is that both research areas have been brought together, i.e. the basic developmental biology research has fed into solving how to differentiate hESCs into beta cells.

What’s your current aspiration?

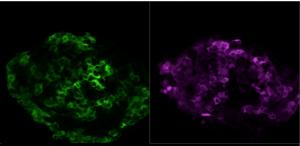

Image: Olle Korsgren.

My current aspiration is to combine the work on pancreas and beta cell development in mice with our hESC work.. The basic biology of how human pancreatic progenitors expand and differentiate into mature beta cells is essential if we are going to be able to manufacture sufficient number of beta cells for the future clinical needs. My feeling is that the field is not acknowledging that many basic research questions remain before we are ready to try the safety and efficacy of hESC-derived beta cells in patients.

What big projects are you working on at the moment?

We are currently trying to fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge of how pancreatic progenitors make the choice to proliferate or differentiate into beta cells, with emphasis on the extracellular cues that control these processes. The aim is to use this knowledge to be able to meet the demands by the regulatory authorities for the mass production of functional beta cells from hESCs before they are tested in patients. We are addressing these problems in our own research group and together with other experts in the field. A single research group will not be able to overcome these challenges. We need to work together!

What advice would you give to a young scientist in this field?

"In the end you have to do the things that you yearn for, the things that are close to your heart."

It is extremely important to get experience by working in different areas relevant to your field of interest. You need to have your own view on where the field stands, and then map out how you want to approach it. Furthermore, you need to liberate yourself as scientist by constantly asking questions and being critical. In the end you have to do the things that you yearn for, the things that are close to your heart. I would never have survived in research if I didn’t do something that I love doing.

More about Henrick Semb's work:

- Henrik Semb's webpage on the Danish stem cell centre's website

- HumEn - a stem cell research consortium co-ordinated by Henrik Semb

Related articles on EuroStemCell

Acknowledgements

Images courtesy of Olle Korsgren.

Last updated: